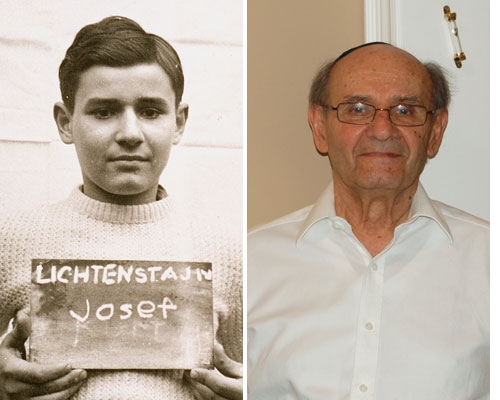

Josef Lichtenstajn Identified

May 2, 2012

Joseph Lichtenstein’s picture was taken at Kloster Indersdorf in September 1945. He comments on the contrast between how he looked at liberation and how he looked in the photo. “From April to September,” he says, “I must have put on quite a bit of weight. A good wind would have blown me away.” After liberation, he tells us, “We never stopped eating.” Describing his time in the camps, he tells us, “It’s a sad situation when you see a father and son fighting over a piece of bread.” The intense hunger that survivors like Joseph experienced during the Holocaust continued to haunt them after the war had ended. When Joseph flew from Germany to Scotland after the war, he and the other boys were given bread. Everyone put the bread in their pockets because they did not know if they would have anything to eat the next day. Joseph believes that he survived thanks to the blessing given him by a rabbi sometime before his family was deported to Auschwitz.

Joseph was born in Satu Mare on December 26, 1929. He was the second of four sons born to Baruch and Sheindel Lichtenstajn. His elder brother was named Moishe (now known as Arthur), and his younger brothers were Yehuda and Shmuel Levi. Baruch was in the textile business and his wife was a homemaker. Joseph recalls a rigorous schedule of religious and secular education. He would get up early in the morning to study at the heder. He would then go to shul to pray and then to school until three o’clock. After school, he would return to the heder until around eight at night. The family lived a fairly quiet life until the war began.

In 1942 or 1943, the Hungarian government decreed that those not born in Hungary would be deported to their countries of birth. Joseph’s father had been born in Poland, so the whole family left Satu Mare to go into hiding for a few months in another town. When things calmed down, they returned home. The family did travel again during the war. At one point, Baruch took his two older sons to Budapest to be blessed by a prominent rabbi who was being smuggled out of Europe. Joseph remembers waiting up all night to see the rabbi. He and his brother went in without their father, the rabbi blessed them and told them they would see each other again some day, and then they went home.

Sometime later, the family was taken to the ghetto in Satu Mare. They stayed there for three or four months before being put on cattle cars and taken to Auschwitz. After three or four days on the train, they arrived. It was at the beginning of 1944. Joseph says, “You can’t imagine what the chaos was.” Dogs were barking at the new arrivals, and people were screaming and yelling.

It was soon after their arrival that Joseph and his elder brother were separated from the rest of the family. His parents and younger brothers were murdered at Auschwitz. After a few days there, Joseph and his brother were sent to Birkenau and then to Buna. They ate whatever they could scrounge and went out to work each day. It was wintertime, and they had hardly any clothes to keep them warm and only wooden shoes to wear.

Joseph remembers waking one morning with a terrible headache. Although it could be dangerous, he went to the camp hospital. There, a French Jewish doctor told him that he had water on the brain. Joseph spent a few weeks at the hospital until he had recovered. He attributes his recovery not only to the doctor but also to the rabbi’s blessing.

Joseph recalls other instances during which his life was miraculously spared. Every morning when the prisoners gathered, a doctor would inspect them. The sick ones would be put on a truck to be taken to the gas chambers. Every barrack had someone in charge to help. One morning, the man who was in charge of Joseph’s barrack had a cousin who was picked to go on the truck. The man in charge switched his cousin for Joseph, who began screaming and crying when he was placed on the truck. “I was on the truck already,” Joseph says. “A miracle happened.” Joseph was taken off the truck, but the other prisoner was sent way.

In January 1945, Joseph and Arthur left Buna because the Soviets were coming. It was the middle of the night and bitterly cold, but the brothers and the other prisoners were dressed only in rags. They marched for two or three days before getting on a cattle car for a couple of days. “This was all without food,” Joseph adds. They ended up at Buchenwald. Sometime later, when it became clear that the Americans were coming, camp officials rounded up a group of prisoners and marched them out of the camp. Joseph and Arthur were separated, and Joseph was led away toward Flossenbürg. “For days and days we marched, without food, without anything…I don’t know how I stayed alive. I don’t know what gave me strength without food walking in the cold for weeks, managing day in and out, sleeping in the open fields with rats and other animals running over me.” He attributes his survival again to the rabbi’s blessing. After a few days at Flossenbürg, Joseph was taken on another death march. Fortunately, the Americans caught up with the group and he was liberated.

Joseph had never seen American soldiers before and didn’t know who they were. The soldiers threw chocolates and chewing gum to the newly free prisoners. “I’d never seen chewing gum in my life, and I chewed it and chewed it and I finally swallowed it.” Joseph wandered the streets and registered as still alive. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) placed him in Kloster Indersdorf. Joseph remembers that the people working there “wanted to give us everything.” They had teachers and good food. He also remembers that he and the other children at the institution found it difficult to sit patiently in classrooms. They had missed out on a lot in their lives and were living free and wild in order to make up for what they had lost.

After a time at Kloster Indersdorf, Joseph went to Glasgow. After a few months, he went to London, where he and Arthur were reunited. The two wanted to go to Argentina, but Canada welcomed them first. They spent time in an orphanage in Toronto before going out to work. After a few years, Joseph met Jean Newton, who would become his wife. He worked for a kosher butcher in Toronto until his brother-in-law told him about an opportunity to open his own butcher shop in Ottawa. Jean’s family was from Ottawa, and they decided to move there. Joseph retired ten years ago. He and his wife are the proud parents of three daughters. They have seven grandchildren.