Abraham Gerecht Identified

December 5, 2012

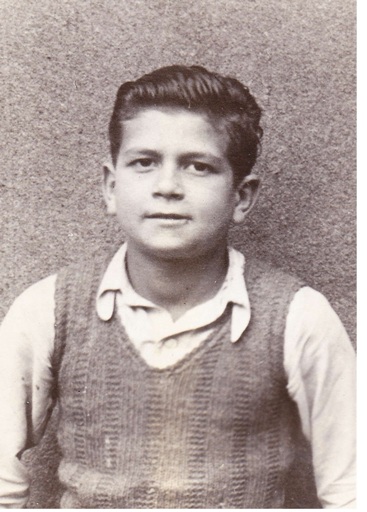

Abraham Gerecht’s picture on the Remember Me? site is the only one he now has from his childhood. His friend Natan Avisar, who told him about the Museum’s project, insists that he looks just the same now as he did when he was a child.

Abraham feels fortunate. He is glad that we contacted him and that someone cares about his life experiences. Abraham gave a testimony at Yad Vashem, but his brother, Marcel, who lives in France, has not. Marcel lived a few years in Israel after the war but then wanted to return to Belgium. Since he could not get a permit to stay there, he settled instead in France near the border with Belgium and has lived there ever since.

Abraham’s parents came to Belgium from Poland in the late 1920s in search of work. His mother, Frieda (Frymet) Rotman Gerecht (born May 15, 1900), and father, Moshe (born May 15, 1891), were from Warsaw. In Belgium, Moshe opened a leather treatment business and Frieda was a homemaker who cared for the children. Marcel was born in March 1932 and Abraham in December 1933. Their parents were not Belgian citizens and the children’s birth certificates indicate that they were Polish.

Both parents were deported from Malines (or, in Dutch, Mechelen) on Transport 8 on September 8, 1942. Abraham received a photograph of his mother and quite a few documents from the museum there. When their parents were taken, both boys happened to have been at a Boy Scout camp at a fortress near the Belgian-French border. When they returned to Brussels, a neighbor told them what had happened and kept them overnight. Their mother had given this neighbor a sack with many valuables before leaving, and these were returned to Marcel when he returned to Brussels in 1956 or 1957.

After they left their neighbor’s home, the boys roamed the streets, sleeping in basements and corridors. It seemed to them like they lived that way for quite some time but neither knows exactly how long it was. Eventually they were taken to Wezembeek and were protected there, along with many other children, by the Queen of Belgium. They were treated well but could not study due to Gestapo rules. They were supposed to be there only until the age of 12 when the Gestapo wanted to take them away. It was probably at the beginning of 1945 when they were sent to live in various convents. They were in a convent in Louven, not far from Brussels, and Abraham has positive memories from that experience. Generally speaking, Abraham thinks that he was very fortunate and that in all the places he lived he was treated well. He attributes his positive attitude toward life to these experiences and tries live life to the fullest.

Abraham thinks that the Jewish Brigade took him and his brother out of the convent and placed them in Wezembeek. His brother wanted them to be religious. Although the family was not very observant, their mother did light candles every Friday night. They were then placed in Marcq-En-Baroeul, France, not far from Tournai in Belgium, on the border near the city of Lille. There was a Bnai Akiva group there and they finally started to study. Three soldiers from the Jewish Brigade were their leaders in the youth movement.

Abraham is in contact with one of the teachers from that school, now a lady in her 90s. After 50 years there was a program to search for the children who had been at the school and there was a documentary film produced as well. One of the teachers interviewed for the film asked for Abraham because she still had a picture hanging in her house that he drew as a child. He sculpts now. This teacher, Jeanne Pecar, was especially kind to Abraham. She rode a bike to school and sometimes allowed him to use it.

Abraham moved to Israel in 1949 and was placed with French-speaking children, some from North Africa. They were sent to Kvutsat Kineret but he did not like it there and soon left for Tel Aviv, where he was homeless until 1951, when he altered his age on his birth certificate so he could join the army. He rose in the ranks but left in 1955. Friends helped him find work and he became a metal worker specializing in copper for decorative and religious works. In retirement he has been sculpting. In 1958 he married his wife, Rivka, with whom he had a happy life for over 50 years. She died five years ago.

Abraham’s son, Moshe, and his family live in Ramat Gan, not far from him. He has taken his two granddaughters to Yad Vashem, where he goes every year to say Kaddish for his parents.

Sylvain Brachfeld’s book, Ils n’ont pas eu les gosses (1989), has information on many Jewish orphans saved in Belgium, including information on Abraham’s and his brother’s childhood during the war. Sylvain convinced him to request and accept restitution from Germany. Abraham says that he has forgiven the Germans, although the pain never goes away and he still cannot read his parents’ names on Yom Hashoah. He has been able to put space between the past and his present life, and he tries to make the most of every day.