Fischer Kampel Identified

February 26, 2013

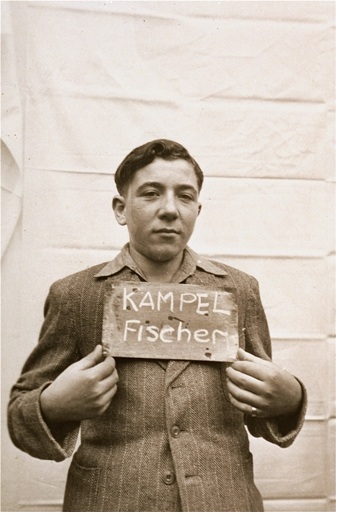

Laurence Kampel lost his father, Fischel, when he was only seven years old and never had the chance to ask his father about his experiences during the Holocaust. We shared with Laurence documents about his father’s time during World War II from the Museum’s International Tracing Service collection; he told us that the records confirmed the information he had seen in his father’s personal papers, but he was amazed and grateful that there is still access to these records. Laurence shared with us what he could about his father’s life after liberation. Born in Bodzentyn, Poland, in 1930, Fischel was the only child of Lebusz Kampel, a merchant, and his wife, Hendla (née Niskier). In 1942, Fischel, his parents, and the other Jews of their town were taken to the camp Starachowice. Lebusz and Hendla were killed there, but Fischel survived and was taken to several other camps: first Auschwitz and then its subcamp Monowitz in 1943, then Oranienburg, a subcamp of Sachsenhausen, in 1944, and finally to Flossenbürg in 1945. In April 1945, the US Army liberated Fischel when he was on a death march from Flossenbürg to Dachau. He was taken to Neunburg, where he stayed for a time with American soldiers. He was taken eventually to Kloster Indersdorf, where his photograph was taken.

After the war, Fischel spent some time at Kloster Indersdorf before leaving for the United Kingdom on October 31, 1945. He went to Windemere, in the Lake District, where he stayed in a hostel, and then, like a lot of the boys with whom he came to the United Kingdom, he ended up in London. There he became a tailor and worked with another survivor until his health no longer allowed him to do so. Fischel lived in a hostel in Finsbury Park, an area of North London, and met Sylvia, the granddaughter of Russian immigrants, in 1954. They married in 1956 and lived in South Tottenham, where Sylvia remained until 1985. She then moved into a small apartment where she lived until her death four years ago. Fischel and Sylvia had only one child, Laurence. They wanted to have more children, but after Fischel was diagnosed with leukemia in 1962 the doctor told them that they shouldn’t have more. Fischel died in 1965, when he was 35 and Laurence was only 7. Sylvia believed that his illness was caused by the work he did in a synthetic rubber factory during the Holocaust.

Fischel never told Laurence anything about his life during the Holocaust, and he never spoke much about it with Sylvia, either. Laurence does have some statements and documents related to his father’s claim for compensation payments from the German government, payments that he began receiving in the late 1950s. When he was in school studying German, Laurence had the documents translated. From them, he was able to learn about where his father was during the Holocaust. Fischel remained friendly with about a dozen fellow survivors in the area, and they met regularly. They were members of the 45 Aid Society, a mutual aid society that Holocaust survivors in the United Kingdom formed after the war. In some ways, the society was like an extended family for survivors, many of whom had lost most or all of their families during the Holocaust. After Fischel died, the society gave Sylvia an allowance to help support Laurence until he was 13. One of the members owned a clothing shop, and once a year Laurence would go to the shop to get new pants and shirts that the society would then pay for. The loss of his father was very painful for Laurence. As a teen, he lost touch with the society. About ten years ago, he realized that the only people who might know about his father’s life during the war would be members of the group. He approached Ben Helfgott, the society’s chairman. Laurence then went with his wife to the society’s annual reunion. The experience proved much more difficult than Laurence had imagined. He recognized about a half-dozen men who had been among his father’s friends when he was a boy. He was able to talk with them about his father, but he didn’t learn anything new about his father’s life. To Laurence, it seemed as though the survivors’ lives had started in 1945, after they arrived in England. Laurence continued to attend the annual reunions for several years, but he was sometimes frustrated by the fact that he was placed with the survivors’ children. Laurence would have liked to spend more time with the survivors themselves because he believed it would allow him to in some way feel connected with his late father. Laurence also found it difficult to spend time around the second generation because he resented the fact that they still had their fathers while he had lost his own when he was so young. “They’ve got something that I never had and always wanted,” he says. When Anna Andlauer began organizing reunions for the survivors who were at Kloster Indersdorf, she contacted the 45 Aid Society, which put her in touch with Laurence. Laurence went to the first reunion that Anna arranged. He says it was very moving to be where his father was after he was liberated in 1945. He met some of the survivors who we have profiled, including Martin Hecht and Hans Neumann. Hans was in Windemere with Fischel and gave Laurence a photo of the two of them together there. Laurence had the chance to meet with Hans a few more times before he passed away. Fischel was an only child, but Laurence has often wondered if there are other family members, perhaps cousins, who survived as well. Several years ago, he sent emails to people with the surname Kampel for whom he had found listings in North America and the United Kingdom. He received no replies. According to Fischel’s Child Tracing Service file, his mother had two brothers, Lebosz and Abraham Niskier, who were living in Brazil after the war. Laurence would welcome the chance to connect with relatives who might be able to tell him more about his father or his father’s family. View Fischel Kampel's Remember Me? profile.