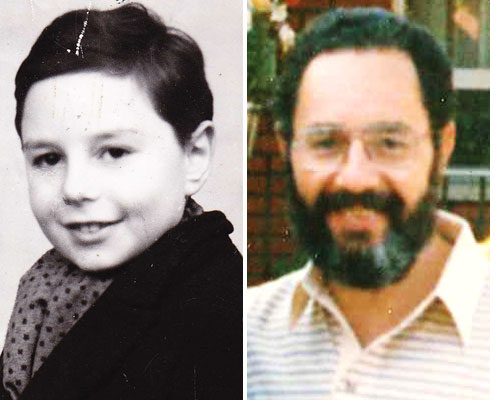

Henri Barik Identified

September 3, 2013

Information about the late Dr. Henri Barik comes from several telephone conversations with his widow, Florence Barik, who lives in Jerusalem.

Florence Barik Googled the name of her late husband one day and found him among the Remember Me? children. She contacted the Museum and was very eager to provide information on his life for an update on the Museum’s website.

Henri Charles Barik was born on June 16, 1936, the third child and only son of his parents, whose two daughters were named Paulette and Raymonde. His mother, Elisheva (Lisa) (née Gutmann), had him when she was in her 40s. His father, Mendel Menahem Barik, originally from Warsaw, worked in the Renault factory in Paris. They met and were married there, probably in 1926.

As the family was preparing for Henri’s sixth birthday in June of 1942, Mendel was rounded up with other men, supposedly because a Nazi officer was shot in Paris. This group of men was sent first to Drancy and then to Pithiviers. The family received a letter from Mendel when he was in Drancy, but the letter was later lost. Henri often relived the trauma of his father’s arrest; Mendel told Henri that he would have to become the “man of the family.” When he spoke of it years later, Henri would always cry.

Mendel Barik was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 35 on September 21, 1942, and, according to camp documents examined by Museum staff, died there on December 3. Henri never knew his father’s exact date of death as he was led to believe that he died upon arrival, which was the eve of the holiday of Sukkot, ironically Henri’s favorite holiday.

According to Florence, all three children were indelibly marked by their Holocaust experiences. All three were very attractive people, bright and charming.The family was religiously assimilated. After Mendel’s arrest, they remained in their apartment, and although everyone in the courtyard knew that they were Jews, no one betrayed them to the police. Lisa did not allow them to wear the required Star of David, and they managed to get by that way because they did not look stereotypically Jewish. All her life Lisa spoke with warm feelings about her French neighbors, who never gave them away.

At the beginning of the war, Lisa cleaned at a restaurant across the street from the apartment late at night, for which she was given leftovers for her hungry children. The apartment house and the restaurant were still there when Florence and Henri visited Paris early in the first decade of the 20th century. Lisa was a heroic woman who resourcefully cared for her children. She was very intelligent and spoke very well several languages. Her French, which she learned as a teenager, was impressive. She was born in a small town in Ukraine, but was raised in Turkey, where her family escaped so that her father would not have to serve in the army. In Istanbul, Lisa was educated at a Scottish missionary school and for the rest of her life spoke English with a heavy Scottish accent. Eventually most of her family made its way to France in search of a livelihood. Lisa was sent there as well when her mother became too ill to care for the family.

As World War II raged on, it became clear that the Bariks would have to separate in order to survive. Lisa sent Paulette, who was 16 when her father was arrested, towork as a nanny near Paris at a home for young children. She was later sent to Hendye, a little village in the south of France near the Spanish border.

Meanwhile, Lisa walked to Lyon, where she had wealthy relatives, sleeping in the woods on her way, but determined to get some money for her family. The relatives were very generous and later in life she often spoke about them with affection and respect.

Henri and Raymonde, his “little mother,” were sent to a farm in Saint-Bohaire southwest of Paris. The school there had his registration records as well as those of his sister. His papers listed him as “quiet and shy but obviously brilliant.” They were on the farm for six months, but when there was no more money to pay for their care, the children had to return home, where they were like “sitting ducks.” Henri saw German soldiers marching in the street and sometimes they would give him chocolate.

Henri had an uncle, Armand, one of his mother’s brothers, who served with the French Foreign Legion for 20 years. Because the officers knew that he was Jewish, during the war Armand was not sent to places where he would have been in greater danger. Armand was able to come to Paris once to see the Bariks. Several other relatives perished in the Holocaust, and Henri made sure to submit their names to Holocaust memorial organizations. His mother was one of 12 siblings, several of whom lived around the world. Henri knew almost nothing about his father’s family except that they were from Warsaw.

After the war, when American GI’s liberated them, Raymonde fell in love with a Jewish-American soldier, but her mother did not want her 14year-old daughter to marry so young. Lisa found a good government job and wanted to stay in Paris, but her wealthy brother who was livingin South Africa pressured her to move to Canada, where they had well-to-do relatives—they had a brother in Toronto and a sister in Ottawa—for the sake of her children’s futures. The family immigrated to Toronto in 1948, when Henri was 12, and stayed with the family. His uncle, with whom they lived for a few weeks, made it clear that it was a temporary situation. His aunt Marie took him to Ottawa to make sure he had a bar mitzvah.

After a while, the family moved into their own home and Henri went to school. Paulette worked in a department store. After Raymonde moved to New York City, Paulette followed her and was eventually promoted to a very responsible position at a large department store. She never married and lives in Manhattan. Raymonde married a Frenchman who was not Jewish and had three children. In retirement she lives in Poughkeepsie, NY, near a devoted daughter.

Henri was left with his mother, who worked in a bakery but was unhappy because she always wanted to return to Paris. As a compromise, they moved to French-speaking Montreal, where their situation was grim. They did not have enough money for food as Henri’s mother had just a menial job. Henri attended high school there and his performance was excellent. The family of a very close friend in high school helped Henri a great deal, but a year before he would have graduated, he and his mother moved back to Toronto. Henri received his degree by attending night school, scoring the highest marks in Ontario. This accomplishment was written up in local newspapers. While studying, he worked in a candy factory and took other part-time jobs to make ends meet. Later, his mother lived on and off near her daughters in New York.

For his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Henri attended McGill University in Montreal on a full scholarship. He received a PhD in linguistics and applied psychology from the University of North Carolina. Because of his charm and likeable personality, several times in his life Henri was taken in by loving families who helped him through challenging times. He worked for many years at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), which is part of the University of Toronto. There he did invaluable work at the Modern Language Centre, especially research on learning a second language. His publications continue to be relevant in the field.

Florence met Henri in 1979, and they had a very happy 30-year marriage until Henri’s death in 2009 after a rapid decline from a particularly debilitating form of dementia. He was a bachelor until the age of 43 and never had children of his own, but he was like a loving uncle to Florence’s two daughters and a grandfather to their children. Henri continues to be deeply mourned by his wife and sisters. His tombstone reads: “A Wise, Compassionate and Generous Man.”