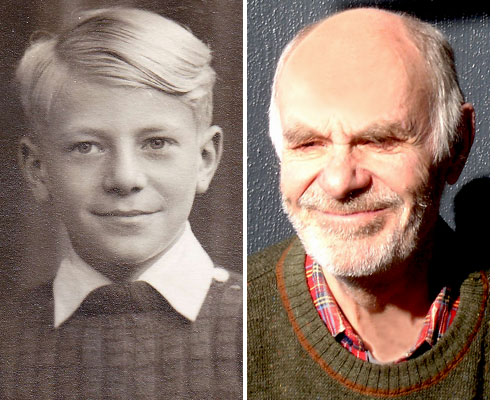

Jacques Herszkowicz Identified

July 15, 2014

Jacques Herszkowicz—who now lives in Denmark and is known as Jacques Hersh—learned about his picture on the Remember Me? website from his niece, who lives in the United States. Jacques recognized his photograph right away and even remembered the sweater he was wearing in the picture. Jacques’s parents, Mordka Herszkowicz and Helen (née Najman), immigrated to France from Poland during the 1930s. Mordka went first and was later joined by Helen and their two older children, Charles and Rosette (also known as Rachla). Mordka was a tailor, and Helen helped out with sewing at home while taking care of the family. Jacques was born in France in 1935.

Jacques remembers being in kindergarten around the time that Germany invaded. Like many other people, he and his immediate family fled Paris at the time of the invasion. Eventually, they returned to their apartment. Jacques remembers wearing the yellow star. By this time, Mordka had died. He had been ill and unable to get the medicine he needed due to wartime shortages.

Jacques also remembers the summer day in 1942 when the French police came to their building and began rounding up Jewish families. Polish Jews were getting notices instructing them to pack their belongings and wait until the police came to get them. Families were being taken in alphabetical order, so the Herszkowicz family was not among the very first to be rounded up. When they were notified, the family packed in preparation for their journey and went into the street, where there was a lot of commotion. Helen was not good at speaking French, but somehow a man began speaking to her. “What are you doing here?” he asked. When she answered that they were waiting for the police to come take them, he told her, “You are crazy. Why are you waiting? You should find out how to get away.” The family’s escape from deportation was thanks to the remarks of this strange, non-Jewish Frenchman.

The Herszkowicz family returned to their apartment. Their sixth-floor neighbors, the Buchwalters, had a daughter, Annette, who was the same age as Charles. The police had taken Annette’s Polish-born parents but left her behind because she was French. Helen asked if they could stay with her a few nights, and Annette was happy to have them. The next day, they heard the police at their apartment, but of course, they did not answer.

Annette provided the family with everything they needed while they stayed at her family’s apartment. After about a week, Jacques and Rosette left the apartment. Jacques remembers that they could not go downstairs during the day because the concierge would recognize them, so he thinks they probably left at night. Mordka had a brother who lived in the suburbs of Paris who had become a French naturalized citizen. Jacques doesn’t remember the details, but somehow he and his sister somehow made their way to their uncle’s home, where he lived with his wife and children. After about four or five months, due in part to pressure from his aunt, his uncle made the two leave his home. By this time, Jacques had learned that his mother and brother had gotten to the French free zone, and Jacques and Rosette, who were then seven and thirteen, set out to join them.

They had to switch trains in one town, where they tried to stay overnight in a hotel. They had no documents with them, so an employee at the hotel called the police, who took them to jail for a week. The police contacted a Jewish organization, and officials from it picked up the pair and took them back to Paris, where they were separated. Rosette went to a home for young girls, and Jacques went to a home for boys in a different part of town. Periodically, the police would come with buses to take away the Polish-Jewish children. Although Jacques was French by birth, Rosette was not. A social worker at the girls home had taken a liking to Rosette, and at one point warned her that the police were coming and her name was on the list of children to be taken away. The social worker wanted to remove her from the home so she would be safe, but Rosette did not want to go anywhere unless her brother was going with her. The social worker told Rosette that there was no need to worry about Jacques because he was French, but Rosette stood firm on the matter. The social worker arranged for both children to escape and hide for a few days in a church’s bell tower while she and her colleagues worked to find them a place to hide in the countryside.

Rosette and Jacques were taken to a farm owned by a French-Polish family. Jacques recalls that they were not treated well and it was very difficult there, especially for his sister, because she had to work. At some point it was arranged that the two children would leave the farm, cross the demarcation line, and join their mother, who was working as a maid, and their brother, who worked on a farm and later in a factory. By the time this happened, it was already 1943, and Jacques recalls that it was a “fantastic reunion.”

The war was not yet over, and it was decided to have Jacques and Rosette smuggled to safety in Switzerland. The family paid a considerable sum of money to do this. Jacques and Rosette took the train to Grenoble, walked on foot through the woods and over the border with a group of refugees, and Swiss soldiers took them to Geneva. They were again separated; this time Rosette was in a home for young women, while Jacques was in Palais des Nations, a League of Nations building that had been converted into a children’s home.

Rosette was eventually sent somewhere in German-speaking Switzerland, possibly Zurich, where she worked in a restaurant or café. Jacques was sent to a children’s home in the Alps where he stayed for some time before being placed with a family who were members of Salvation Army, and who took in children and fed them, probably with help of money from the Red Cross. Jacques remembers them as very nice people. By the time he arrived at their home, Jacques was tired of moving from place to place, and he had not wanted to leave the children’s home in the mountains. He tried to make life impossible for the family. They knew his background and didn’t try to influence him, though he went to their religious services and even collected money for them. Jacques recalls celebrating Christmas with them as a beautiful experience, especially because of the snow. Rosette visited him once while he was there.

After the war, Helen and Charles returned to Paris and made arrangements for Jacques and Rosette to return as well. Their apartment had been taken over by someone else during the war, but Helen was able to get it back. The family stayed in Paris from May 1945 through 1949, with Charles and Rosette both working to support them. Helen had a brother who had gone to Palestine in the 1920s and another brother, Jack Najman, who had gone to New York. Both brothers wanted the family to join them. Rosette and Jacques wanted to go Israel, but Helen and Charles wanted to go the United States, so that is where they moved. Jacques attended junior high and high school in New York. He found it challenging to get through school while learning to master the English language. After graduation, he worked evenings and summers to pay his way through the City College of New York. He delivered newspapers and served as a soda jerk, a dishwasher, a waiter, and a busboy.

After finishing college, Jacques joined the US Army for two years and was stationed in Germany. He returned to the United States and worked for a while before deciding to go to study in Vienna. There he met his wife, Ellen Brun, who is from Denmark. They have been together for 50 years. After a year and half in Vienna, Jacques and Ellen went to Copenhagen. There, they both earned doctorates in sociology, and he became a professor in development studies and international relations at Aalborg University. His brother and sister both passed away in their 50s, and Jacques is now retired.

View Jacques Herszkowicz's Remember Me? profile?