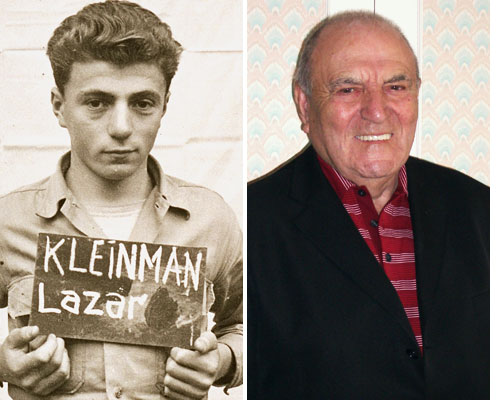

Lazar Kleinman Identified

September 27, 2011

Leslie Kleinman, formerly Lazar Kleinman, was born in 1929 to Martin (Mordka) and Rosa, Hasidic Jews who lived in the small village of Ombod in Romania, near Satu Mare. Martin was a rabbi and Hebrew teacher in Ombod. Leslie had seven siblings: Gitta, Herman, Olga, Irene, Ilonka (Chaia Sara), Abram, and Moshe. Leslie was the second eldest of his siblings. He had indeed seen this photo before. He knew it had been taken in the postwar era at the Kloster Indersdorf displaced persons camp. In July 2011 Leslie returned to Indersdorf, Germany, to attend the annual reunion, organized by Anna Andlauer, of child survivors who lived there.

Leslie vividly remembers being moved into the ghetto in Satu Mare on Shabbos morning the first week of April 1944. His father had been taken to work on the Russian front three weeks earlier. Leslie painfully recalls his father’s goodbye: “My mother was crying and said, ‘We will never see you again.’” His father disagreed with her, saying that he would be home in no time. Leslie never saw his father again. He also remembers riding the train from the ghetto to Auschwitz, where he arrived on May 16, 1944. “It was so crowded, and the children were all screaming.” Upon arrival at Auschwitz, the Kleinman family stood in a single line waiting to be addressed and questioned by camp guards. A small group of Polish Jews spoke to Leslie in Yiddish and asked him how old he was. When he replied that he was 15 years old, they suggested that he lie to the guards and tell them that he was 17. Then they said,“You will be all right.” Unbeknownst to Leslie at the time, this lie would make him more likely to be chosen for forced labor in the camp. The guards moved Leslie into a line to the right while his mother and seven siblings were moved to the left. Leslie went on to stand in more lines that day: the line where his clothes and shoes were taken away and he was given a prisoner uniform and a pair of wooden clogs, as well as the line where his Auschwitz prisoner number, A-8230, was tattooed on his left forearm. Later, during his first night in Auschwitz, he asked the other prisoners in his barracks where his mother and siblings were. They told him that they had been murdered by gas, and that their bodies had probably already been cremated.

His labor assignments in Auschwitz-Buna included working on the camp’s railroad tracks, unloading cement from train cars, and mining coal. On January 17, 1945, as Russian liberating troops got closer to Auschwitz, Leslie and other prisoners were transferred to Oranienburg, north of Berlin. He remembers wondering about the guards there, “What do you guys want from me? You’ve taken my family. You’ve taken my dignity, but you will not take my soul.” He then made a promise to God that if he survived he would spend one year in a yeshiva, studying the Talmud and the Torah. Almost instantly a camp guard appeared with bread and coffee for the prisoners. Leslie considered it a sign from God. Later, Leslie was transferred to Flossenbürg in Bavaria, Germany. “The thing I remember about Flossenbürg is the lice. There were lice as big as my fingernail there. It was terrible.”

Leslie was liberated while on a death march to Dachau on April 23, 1945. He remembers marching through the forests and watching his fellow prisoners who couldn’t walk any further being shot by the camp guards who were escorting them. Zoltan and Erwin Farkas, two Jewish brothers, helped save his life during this ordeal. Weakened by starvation, Leslie could barely walk; Zoltan and Erwin helped him to continue on and let him lean on them when he didn’t think he could go any further.

Leslie still recalls meeting an American for the first time on April 23, 1945. He was lying in a ditch by the side of the road, exhausted, sick, and starving, when someone appeared above him. The man asked him, “Are you a Jew?” When Leslie confirmed that he was indeed Jewish, the man said, “Shalom, I’m a Jew from New York.” The soldier took off his army jacket, wrapped it around Leslie, and carried him to an American Army field hospital. Leslie doesn’t recall the name of the American Army sergeant who helped save his life, but to this day he still cherishes his coat. He would like to thank this American and all the Americans in the Army field hospital where he was treated in Bavaria. He considers April 23, his liberation day, to be a holiday, and he celebrates it every year.

Leslie arrived in the Kloster Indersdorf displaced persons camp on August 27, 1945, and was reunited with his friends Zoltan and Erwin. Greta Fischer, one of the administrators at Indersdorf, took Leslie to Regensburg, Germany, to buy him a suit to wear before he emigrated to England in November 1947. He wants everyone to know how wonderful people were to him after the war. The nuns at Kloster Indersdorf, Greta Fischer, and the American soldiers who would occasionally drop in on the children to check on them “were very kind to us.” When he arrived in England he stayed in a Jewish hostel in Manchester. He kept his promise to God and went to yeshiva for one year. After that he worked in the East End of London helping to make handbags, buttons, bows, and belts. Leslie went on to open his own dress manufacturing company, Roslyn Fashions, whose labels read Eve Rose of London. He married his late wife, Eve, in 1956. After having lost nearly all of his relatives, Leslie “wanted a family more than anything.” In 1979 Leslie and Eve moved to Canada. They were married for 49 years before Eve’s death from leukemia in 2004. Leslie and Eve had two children, Roslyn and Steven. Leslie has one granddaughter.

Several years after Eve’s death, Leslie moved back to England to be close to his daughter. At the age of 83, he married his second wife, Miriam, on April 3, 2011, in Tel Aviv. Leslie considered himself to be nonreligious for about 40 years. Now, however, he lives close to a synagogue, where he goes to pray every morning. He also speaks frequently about his wartime experiences. His favorite audiences are schoolchildren and teachers. “I don’t hate anyone. From hate everyone suffered. We should have love for one another. I speak from my heart. I lost all of my family because of my faith. I want you, your children, and your children’s children to remember.” He wants to spread this message to everyone.

Leslie returned to Auschwitz as a free man on May 16, 2011, the anniversary of the day he arrived there as a prisoner 67 years earlier. There he lit nine candles and with a rabbi said Kaddish, the Jewish prayer of mourning, for the members of his family who died in the Holocaust.