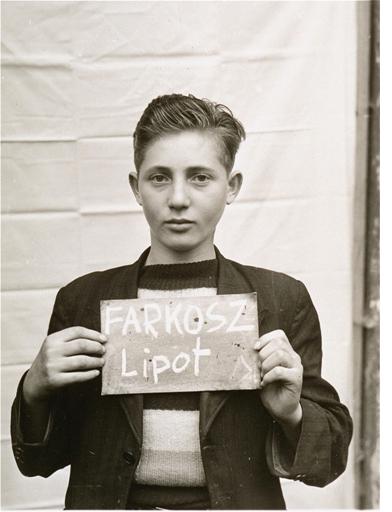

Lipot Farkosz Identified

June 1, 2011

For a period after the war, Zoltan Farkas used the Yiddish name Lipot as a means of asserting his Jewish identity. Zoltan vaguely remembers when this picture was taken and has seen it before. He told us that there is a similar photo of his brother Erwin that neither the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum nor the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York has in its collection.

Born in late 1927, Zoltan was one of five children. His father had two additional children from his first marriage. He lived in a village called Ombod near the city of Szatmar in Transylvania, then in Romania, and was raised in an Orthodox family. Zoltan remembers friendships between Jews and Gentiles, among both children and adults, in his village. However, he also remembers antisemitic incidents such as name calling and rock throwing, which were usually the actions of other youngsters; adults who had such sentiments usually kept them quiet unless they had had too much to drink. Even with these reminders of the animosity that others felt toward Jews, Zoltan never anticipated the destruction that would be carried out during the Holocaust. Even when they began to hear about what was happening in German occupied lands, he and his family did not expect systematic murder to be carried out on the scale that it was.

In 1940, Germany gave part of Transylvania, including the region where Zoltan’s family lived, to its ally Hungary. In spite of the relationship between Germany and Hungary, Hungarian Jews remained relatively safe until the spring of 1944, when the deportations began. Zoltan’s father was taken away by the police. The rest of the family, like all Jews in the community, had to register and wear the yellow star. Soon thereafter, Zoltan and his mother, brother, three sisters, and grandfather were summoned to a school and allowed to bring only a handful of belongings. They were taken to Birkenau.

When they arrived, Zoltan and Erwin were separated from the rest of the family. They never saw their mother, sisters, or grandfather again. The brothers were taken to nearby Auschwitz where they were given uniforms and their prisoner numbers were tattooed on them. Zoltan was prisoner A-7897 and Erwin was A-7899. They were then marched to the work camp Buna where they worked for I.G. Farben Industries. As Zoltan notes, the famous writers Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi both spent time at Buna. Zoltan was there several months. He recalls the harsh conditions, which included a starvation diet, periodic delousing, and several selections that resulted in weaker prisoners being sent back to Birkenau to be gassed. He also recalls several occasions when the entire camp was forced to watch as prisoners were hanged as punishment for minor infractions, and he remembers the factory there being bombed.

The only time that Zoltan and Erwin were separated was when they were evacuated from Buna during the winter. The Soviets were approaching, and camp guards forced those who were able to march in groups of 3,000. The brothers later found each other in a barn where they had stopped. They arrived at the camp Oranienburg, where they did no work. They were then marched to Flossenbürg, where they again did no work. Conditions were terrible there: The prisoners slept in overcrowded bunks, were covered in lice, and faced the constant threat of being beaten. They were evacuated from the camp as the American forces drew near. Zoltan remembers seeing prisoners who were wounded by bullets that had been shot from American planes and penetrated the train cars. When the train became inoperable, Zoltan and his brother were forced to march. Zoltan later learned that they were going to Dachau. They never made it, though, because the Americans liberated them.

Zoltan remembers an American soldier making a German POW give Zoltan his boots to replace his wooden prisoner shoes. After a time, Zoltan and Erwin made their way to a hotel in Swandorf, where the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency welcomed survivors. Here Zoltan saw Jewish women for the first time since he had been separated from his mother and sisters at Birkenau. Until he arrived at Swandorf, he had thought that the Nazis had killed all of the Jewish women. Zoltan and Erwin then went to Kloster Indersdorf. Erwin remained there, but Zoltan journeyed back to Romania for a time. He found friends and relatives who had survived, all of whom were aged roughly 16 to 30. No one younger or older was still alive.

Zoltan and Erwin’s father had siblings and cousins in New York. Zoltan’s friend Miklos Roth had family in New York, and Miklos asked his aunt and uncle to find the addresses of Zoltan’s relatives for him. Zoltan and Erwin arrived in the United States in December 1946 and were at Ellis Island over Christmas. Zoltan then stayed with one aunt and his brother with another. The brothers worked for their uncles and went to college at night. Zoltan studied electrical engineering and had a scholarship from General Electric. He was drafted into the army and later went to the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. Zoltan moved to California in 1962 to work at the Sanford Linear Accelerator Center. He retired about 10 years ago, but he still goes in to work. His brother Erwin became a psychologist and lives in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area.

In 2008, Zoltan and his brother attended a reunion of former Flossenbürg prisoners who had stayed at Kloster Indersdorf after the war. There is now a high school there, and the survivors in attendance met with the students and were treated like VIPs. Zoltan and Erwin also went to Dachau for the first time.

Zoltan is a member of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and in 2005, he donated a collection of photographs related to his life during the 1930s and 1940s.