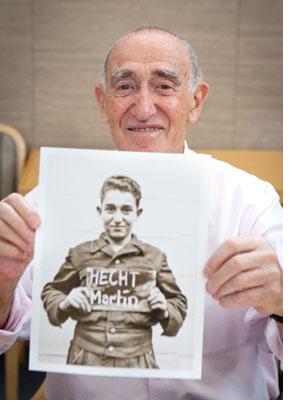

Martin Hecht Identified

May 30, 2011

While preparing for their May 2011 trip to visit family in New York, Martin Hecht and his wife, Aida, who live in Israel, decided that this would be the year that they would take a side trip to Washington, D.C., to visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Just a few weeks before their trip, Martin’s niece e-mailed him to tell him that she had seen his picture on the Remember Me? website. Martin has seen the photo before and has a copy of it. He tells us that he is wearing a discarded Hitler Youth uniform that was found at Kloster Indersdorf after the war. He has attended a few reunions of the displaced children who were at Kloster Indersdorf under the care of Greta Fischer and others. Eager to take part in this project, he spoke by phone with a historian in the Museum’s Holocaust Survivors and Victims Resource Center and agreed to meet with Museum staff members while he was in Washington.

Born in the village of Ruskova in Transylvania at the end of 1930, Martin was the youngest of eight children. His parents were observant Jews and well-to-do landowners. In 1935, his father took four of his children, two sons and two daughters, to Palestine in order to make preparations for the whole family to move there. He returned to Romania in 1938 with his son Samuel, who was too young to be left in Palestine with the other children, in order to sell off the family’s property. He had visas to take the rest of his family back to Palestine with him, but the outbreak of World War II put a halt to his plans.

In 1940, the region where the Hechts lived was taken from Romania and given to Hungary. Martin recalls that, until 1944, life went on as normal in his village. Without newspapers or radios, his community was unaware of the destruction being wrought against European Jewry by the Nazis and their allies. In 1944, German soldiers passed through his village en route to the Ukrainian border. It was a Friday, and Martin was hurrying to be home by sundown on Shabbat. He recalls being excited to see horses, mules, and soldiers. The soldiers stayed only a few days before moving on. A few weeks later, though, the Hungarian police came. Working with the SS, they rounded up the inhabitants of Martin’s village, some 3,000 Jews, and took them to the nearby town of Viseu de Sus. He had an aunt who lived there, and it was the first time he had seen electricity or running water. The family was placed in the ghetto there for about three weeks before being put on cattle cars and sent north. They stopped in Sighet, where Elie Wiesel lived, and then were taken to Auschwitz.

After the family arrived in Auschwitz, Martin and his three brothers were separated from his parents and sister. He never saw his parents again, but his sister survived and has lived in Israel since 1945. Martin and his brothers were never given tattoos because of the large numbers of prisoners being brought into the camp at that time. He and his brothers were given uniforms and taken to nearby Birkenau. After about two weeks, they were put on a train. Five or six hours later, they arrived at Dörnhau, a forced labor camp, where they worked on building a railroad through the mountains. They lived under horrible circumstances and were given little to eat. Nevertheless, Martin was determined to survive. He sometimes took chances, sneaking out at night to steal bread for himself and his brothers from the canteen. Had he been caught, he would have been shot. He says that the fact that he had lived and worked on his family’s farm helped because it had made him stronger and tougher. He noticed that boys from the cities died very quickly in the camps.

Despite the danger and harsh conditions in which they lived, the brothers remained alive and together at that camp for five or six months. At that point, the SS officers rounded up about 500 or so of the youngest prisoners in the camp, telling them they were being taken to a children’s home. Martin and Jack, the next youngest brother in his family, were among those 500, but then a kapo removed them from the group and replaced them with two other boys. Martin later learned that the children in this group were taken back to Auschwitz and murdered. He still does not know why he was saved.

Martin was moved from this camp with his brothers. At one point while they were preparing the prisoners for a death march to another location, the guards separated them into two groups. Martin and Jack were placed in one group and their two older brothers were placed in another. Martin recalls marching forward alongside Jack and being startled by the sound of shots that killed those in the second group, including his two older brothers. Later on, when the guards began to separate the prisoners into two groups again, Martin clung to Jack’s hand with all his strength so that they would not be separated. The guards pulled them apart, but there was so much commotion around them that they were able to find one another and stay together.

The last camp where Martin and Jack spent time was Flossenbürg. Martin has visited the memorial site at the camp and has seen his and his brother’s listings in the prisoner intake ledger there. Jack was prisoner number 80300 and Martin 80301. As the war drew to a close, Martin, Jack, and others at Flossenbürg were again put on a death march. They were en route to Dachau but did not make it there. At the town of Stamsried, they encountered American soldiers, some of them Jews who called to them in Yiddish to get behind the tanks. They were soon liberated. Martin and Jack went to a German home. The woman who lived there ran away. Covered in lice, they washed up the best they could and found food and fresh clothing. After a few days, they were picked up by American soldiers who took them to Neuberg. They were briefly in a displaced persons camp there, but due to the antisemitism they encountered there, they were taken to Kloster Indersdorf.

Martin remembers that there were many babies there, the abandoned children of non-Jewish slave laborers. He also remembers the kindness of Greta Fischer and the nuns who took care of them. He and Jack eventually made their way to England. They spent time in hostels and went to school before beginning their work lives. He married Aida in 1998 and, ten years later, they moved to Israel. Aida tells us that Martin never really spoke about his experiences during the Holocaust until he began attending reunions of the Kloster Indersdorf children a few years ago. He had never spoken to students in England but now talks to students in Germany whenever he goes there. He feels that although German young people of today do not bear personal responsibility for what happened, the German nation is responsible and that therefore they must continue to learn about this part of their history.