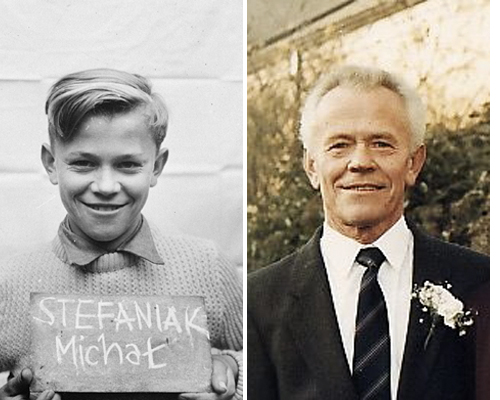

Michał Stefaniak Identified

August 14, 2012

Michał Stefaniak passed away in May 2011. His son, Peter, found his father’s picture on our site a few months later. He sent us the following description that his mother wrote based on her knowledge of her late husband’s wartime experiences.

Firstly I will try to give an explanation of how Michał came to be alone in Germany as a young boy at the end of World War II. This is my version of what he told me. He didn’t tell the story all at one time; in fact, I only learned many of the details gradually over the course of our married life. This might have been because of his limited English earlier in our relationship and his reluctance to talk about his childhood, perhaps because it was painful. He also might have wanted to distance himself from his past and not be associated with the humiliations he felt at that time.

Michał was born in Bachow in southeast Poland to Antoni and Eva Stefaniak. He had two older brothers, Stefan and Vasel; a sister, Maria; and a younger brother, Ganek.

In the early 1940s (he thought this was the date), the Soviet army that had been camped on the opposite side of the River San for some months ordered the villagers to move. The people went in horse-drawn carts to a train station and then took a long train journey. Michał had no idea of where he was in Poland. The people were put in vacant houses, larger ones than in Bachow, but several families were put in each house, causing overcrowding.

After a short time his mother became ill and died. His father became very quiet and appeared to be in a state of misery. There was very little food. Each day, Michał and his younger brother went into a nearby field and ate turnips and pea shells. The women in the house looked after his sister. His two older brothers didn’t seem to be in the house a great deal.

Michał didn’t know how it was arranged but a woman came and told him to go with her. Michał was never really sure if she was trying to help him or if he was just useful to her. They walked a long distance to the small farm in a remote area where she lived with her husband. There was a similar small farm next door. Shortly after his arrival he was told that his little brother had died. Not long after, he was told that his father had died as well.

Michał had to work each day herding a small group of cows and sheep in a forest with areas of dangerous marsh ground. He was accompanied by two dogs. I think he was quite scared as a few wolves came around, but the dogs’ barking discouraged them from attacking the animals. He was by himself from morning until evening. The people he lived with seemed quite uncaring towards him and when one of the sheep was lost, he was beaten up as punishment. He said that this was the worst period of his life. He stayed at the farm for at least two winters.

I don’t know any details, but fighting broke out between Russian and Ukrainian soldiers (Michał thought this was who was fighting). Michał must have moved away from the farm, as he remembered being with some men whom he didn’t know. They told him not to go in the hedges, but to hide in a potato field with them. They spent a night of terror in the field as barns with animals in them were burned down. The soldiers moved away. I do not know the timing, but there had been fighting at a station and there were dead bodies lying about. By this time German soldiers had arrived in the area.

The people were told by the German soldiers that they would have work, and they were taken by train, in the type of carriages without windows, on a long journey into Germany only stopping briefly to take on water. What happened after this I don’t know, but Michał just said he went to work at a farm where, although he had to work very hard, he was treated well by the farmer. He looked after a herd of cows that did not go out into fields but just lived in farm buildings. Eventually the farmer was called up for military service, and the farm was then run by his wife, a young Polish man and woman, Michał, and a German woman working part time. Michał said he always considered himself very lucky to have been at such a decent farm.

The war ended and Michał was then in a camp, which he said was very unpleasant and where it was difficult to get food. He eventually arrived at a children’s home, where he was cared for by members of a religious order. After a time he moved to another children’s home that was only for Polish children; there were other homes nearby for children of different nationalities. He enjoyed his time there going on trips and rowing boats on the lake with the other boys.

It was from this home that Michał, two boys, and a girl left without telling anyone.

They had found out that they were to be sent back to Poland. Because none of them had any family to go back to and because the Russians were to be running the country, they felt there was no future for them in Poland. They took a train to Rosenheim, where they contacted an aid organization that made arrangements for them to leave Germany. They went by army truck to Ancona in Italy. Michał stayed there for a short time before traveling by train and ferry boat to England, arriving in Dover.

Many Polish people were brought to England after the war, and Michał spent a year or more in different camps. He had a few jobs, including one in a garage in London that he enjoyed. The Polish authorities who looked after Poles in England arranged for him to take a course at a college in Liverpool, which served as a stepping stone for a job in the merchant navy. He first went on English ships and then Scandinavian ships, working in the ships’ engine rooms. He loved the life of a merchant seaman and travelled the world for 10 or 11 years. He always stayed with a Polish family in Liverpool between ships.

Michał and I married in 1964 and had two boys. Michał worked at Courtaulds nylon factory until it closed down in 1981. He then converted his interest in gardening into a job and worked at garden center before working for himself. We had a good life together and when the boys were young we enjoyed holidays in Scotland, mainly the west coast. After the boys grew up, Michał and I went on holidays abroad, visiting Poland four times but only returning to Bachow once for about two hours. None of his family had returned. All the original houses had been burned down by the Russians. Later, we traveled to America on two occasions to visit our son who lives there.

Michał kept the photos of his time in Germany and from the camps in England in a tin box that must have travelled the world with him. He didn’t look at them often. When he got to the children’s home in Germany he at last must have been able to be a boy again and have companions of his own age. When the opportunity arose to leave Germany with his companions, I am sure he did not hesitate to go along with the plan, which fortunately seemed to have worked out very well for him. He did his best to fit in with his work colleagues and neighbors and always said he was glad he didn’t go back to Poland.