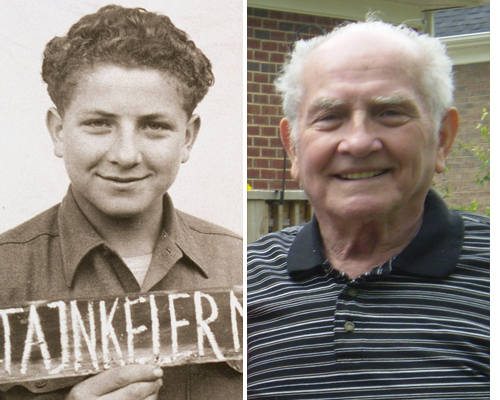

Moszek Sztajnkeler Identified

January 20, 2016

Born Moszek Sztajnkeler in 1928 in Zakrzówek, Poland, Morris Stein passed away in North Carolina in 2014. His son, Jack Stein, says that Morris struggled to talk about his experiences during the Holocaust. As a child in Israel, Jack did not ask his father about his life during World War II because it caused him so much pain. Many years later, during the 1990s, Jack’s younger brother, Harry, worked with their father over many months to record his memories of life before and during the Holocaust.

Morris was the youngest of four children. His father, Jacob, was a cattle trader, and his mother, Hinda (née Bludman), was a housewife. He had two older sisters, Itzke and Chaike, and an older brother, Meir. Morris was almost 11 when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. German troops passed his hometown a number of times over the next year, but it was not until the end of 1940 that they began stopping and taking groups of Jewish boys. They said they were taking the boys for work, but no one ever saw them again. In early 1941,the Germans ordered Jews in Zakrzówek to wear the yellow star. Morris remembered that in the morning he would see the bodies of his fellow Jews who had been shot dead in the streets the overnight.

Later in 1941, German forces ordered the town’s Jewish community to move to another town about ten miles away. Morris’s family decided not to go. Jacob and Meir joined a partisan group, and Jacob became one of its leaders.Itzke and her boyfriend joined a different group of partisans. Morris, Hinda,and Chaike hid in the attic of a farm house in a nearby village in exchange for monthly payments to the farmer. Jacob and Meir periodically visited the farmhouse, bringing food and money. After hearing that the village would be searched for people in hiding, Jacob warned his wife and children. They left for another nearby village where Jacob had arranged a hiding place for them.

A few days later, Morris was on his way back to their original hiding place to see if it was safe to return. He was caught by two Polish guards and taken to prison. A few days later, the Polish police handed him over to the Gestapo. The Gestapo interrogated him. When he wasn’t able to answer their questions, they beat him with a leather strap while a German shepherd bit him. Finally the interrogation ended. He was taken to a prison where there were about 50 other Jewish men, women, and children. A few days later, seven men and seven women—including Morris—were selected from the group and taken to the camp Budzyn. Morris later learned that those who were not selected had been shot.

There were about 5,000 people in Budzyn when Morris arrived, including some of his neighbors and relatives. Every morning he was marched to work digging out tree stumps. Morris remembered suffering from a bout of typhus. Each day the Germans removed the sick prisoners from the camp and killed them, but Morris somehow managed to avoid this fate. The following year,he was taken to another camp, near Cracow, called Mielec.

While he was in Mielec, Morris worked building airplanes. He learned from other prisoners that the Germans had killed his brother and his sister Itzke. He also found out that his father was injured in an anti-German operation and had hidden with his mother and sister Chaike at a farm. Later,Polish police and the Gestapo attacked the farm, killing them all. Morris had been in Mielec for a year when Soviet forces approached the area. He was taken to Wieliczka and then to Flossenbürg.

Morris arrived at Flossenbürg on August 4, 1944, and was assigned prisoner number 16355. He remembered that there were prisoners from many different nationalities there; most of them were not Jewish. At Flossenbürg he worked on airplanes. He later recalled that that he and his fellow prisoners were poorly fed and that many died of starvation. There were no doctors and no medicine, and those who got sick worked until they died.

In 1945, Morris and his fellow prisoners began to see American and English planes flying overhead almost every day. In March, he and the other Jewish prisoners were put on a train to be sent to Dachau. Once the train began to move, the Allies attacked. The prisoners tried to escape but were retaken by their guards. They then set off on foot, sleeping in the woods during the day and marching at night. Morris remembered eating “grass, roots,even leaves—anything that was chewable.” Occasionally German villagers would give them water and scraps of food. After about two weeks, the guards left them. They heard shooting and bombing and saw German soldiers running away. Morris and a group of prisoners made their way to a village where they were greeted by women and children who fed them and told them the Americans had arrived. It was April 23, 1945.

Morris found the idea of liberation unbelievable. He remembers being afraid that the Germans would come back and take them back to a camp or kill them. After a few days, the US Army and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) gave them documents stating that they were displaced persons (DPs) and sent them to a camp in the nearby town of Schwandorf. On the way, they stopped in empty homes that Germans had abandoned and took clothes to replace their prisoner uniforms. Rather than living in the camp, Morris and three other boys lived in an abandoned house. They would gointo the camp from time to time to get food. Sometimes nearby farmers who learned that they had been in the camps would give them food. With guns they had found in one of the abandoned houses they would stop former German soldiers and take away their bicycles and watches. They sold the watches to other DPs to buy food.

Morris was registered to emigrate to England. Before doing that, though, he and a friend decided to go to Poland to sell some of the watches they had stolen. Before they could return to Germany, they were caught trying to exchange Polish money for German marks on the black market. When they were brought to court, the judge recognized Morris as a fellow former prisoner.The judge let Morris and his friend go and helped them to change their money before they left.

Morris made his way back to Germany and spent some time in Kloster Indersdorf. In October 1945, when he was almost 17, Morris left with a group of boys for England. There for a time he was under the care of the Committee for the Care of Children from the Camps. He worked in a meat-processing plant before going to Israel, where he met Rivka Pichota, the daughter of Russian Jews who had moved to Palestine before World War II. Morris and Rivka married in 1949. They lived in Tel Aviv,where their three children, Jack, Betty, and Harry were born. Wanting better opportunities for their children, Morris and Rivka moved their family to the United States in 1961 with the help of Morris’s friend and fellow survivor, Steve Israeler (Remember Me: Displaced Children of the Holocaust). Steve visited regularly and helped them get situated in the Bronx. Thanks to an uncle’s help, Morris became a butcher. As part of the US citizenship process the family changed its name to Stein, and Rivka became Michelle.

Jack speaks with pride of his father’s efforts to support his family. After working as a butcher in New York, Morris took his family to Dayton, Ohio, where he worked for a time for a friend who sold prefabricated homes. He then moved his family to Pittsburgh, where he opened the Tel Aviv Self Service Kosher Meat Market on Murray Avenue. The business was a huge success and Morris later sold it. Having grown tired of Pittsburgh winters, he and Michelle moved to Florida, where Harry lived. When Harry and his family moved to Texas,Morris and Michelle moved to North Carolina to be near Jack and his family.(Betty lives in Delaware). Morris died in 2014, and Michelle passed away in 2015.

Before Morris died, he was contacted by Anna Andlauer, who has organized reunions for survivors who were at Kloster Indersdorf after liberation and has written a book about the UNRRA’s work there. Morris shared his brief memoir with her and provided her with additional information for her book. Anna was able to travel to the US Air Force base in Germany where Jack’s daughter Erika is stationed to do a presentation about Kloster Indersdorf for Erika and her fellow service members. After his parents passed away, Jack and Erika visited Anna and her husband in Bavaria. She showed them Kloster Indersdorf, where Jack knows his father had been happy after the war. She also took them to Flossenbürg, which was a very sad and emotional visit.