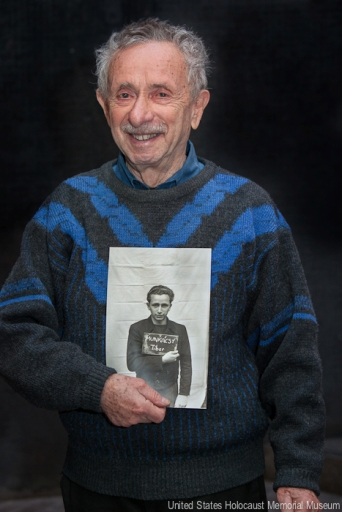

Tibor Munkácsy Identified

January 10, 2012

Now known as Tibor Sands, this survivor is very familiar with his photograph. It was used for his passport to go to England, and he still has a copy of it. This photo was very helpful in reuniting Tibor with family members, but not in a way that would be expected. When his photo was taken at Kloster Indersdorf, Tibor mentioned to the American photographer, Curt Riess, that his older brother lived in New York. The photographer laughed until Tibor told him his brother’s name. Riess knew Tibor’s brother, Martin Munkácsi, a prominent photographer who had worked for Harper’s Bazaar. Riess helped Lillian Robbins, a UNRRA official at Kloster Indersdorf, get in touch with Martin on Tibor’s behalf.

Tibor Munkácsi was born in Budapest in December 1925. He had ten older half brothers and half sisters. His father died when he was five. His mother supported her family dealing in used clothing. Growing up, Tibor was cared for by a sister who was 17 years his senior. He went to school and was a very good student, but he quit studying when he had a teacher who was an antisemite. He then apprenticed as a tailor and worked at this trade for a few years.

In May 1944, Tibor was drafted into a Hungarian battalion doing forced labor. He and his comrades were working near the Romanian border. With the Soviets advancing, Tibor and a group of about 16 or 18 Hungarian Jews formed a fake detachment and hitchhiked back to Budapest aboard a German armored train. This was very risky, but the Germans were themselves retreating, and the group was able to make it safely to Budapest.

In Budapest, Tibor lived in hiding. His mother and sister were there as well, but it was not safe for him to stay with them. Tibor hid in various places. For a time, he slept in the quarters of the Jewish labor company. During the day, though, he wandered around the city. He had changed his birth certificate so that it said he was Catholic instead of Jewish. “It looked very good, actually,” Tibor recalls. One night, Tibor and a few others were discovered by Hungarian Nazis. Tibor produced his birth certificate, but one of the Nazis recognized him from elementary school and knew that he was a Jew. Tibor and his comrades were taken to a school and lined up against the wall to be shot. At the last moment, an army lieutenant from the labor company appeared and placed Tibor and the others under arrest. He led them three blocks away from the school and then set them free.

Afterwards, Tibor slept a few more nights with the labor company. One morning, in November 1944, the Hungarian military showed up and surrounded the school where the company was quartered. The Jews inside were brought out and marched down a wide street toward the Danube. A smaller young man, Tibor lagged a bit behind and pretended not to be with the company in order to escape. When he reached the rear of the group, he told a gendarme that he wanted to speak to the Jews, to which the gendarme shouted “No!” He then threw Tibor to the sidewalk. Tibor had nowhere to go. A Christian friend was able to put him up for a few nights, but then the friend’s father said Tibor had to leave because his presence placed the rest of the family in danger. Tibor says, “I didn’t blame them then, and I don’t blame them now.”

Not long afterward, Tibor was caught again. This time he was locked up in a building near his birthplace. On his birthday, December 9, the building was emptied. Tibor and the others there were marched to a railroad station and put into cars. Twenty to thirty cars full of prisoners arrived at Buchenwald many days later on December 25, 1944. Tibor was first placed in a quarantine camp and managed to find a German kapo who was in charge of the tailor shop. Finding work as a tailor probably saved his life, as it kept him from working on a construction detail out in the cold. Tibor worked inside until early April, when he and the rest of the Jews at the camp were evacuated. First they marched and then they rode trains and trucks until they arrived three to five days later at Flossenbürg. They spent the night there in jail and then left the next morning in trucks headed for Dachau. On April 23, they spent the night in a barn along the road. The next morning, the SS men ran away just a few minutes before the Americans arrived. They drove up in jeeps, some of which had the bodies of SS men draped over their hoods.

After liberation, Tibor had a big sore on his foot that would not heal. He stayed at a field hospital for a time and eventually went to Kloster Indersdorf. There he met Riess, the photographer who knew his brother Martin. Martin had moved to the States between 1934 and 1938 along with Tibor’s two other older half-brothers, Adolf and Muki. Martin didn’t approve of his father’s remarriage and had little to do with Tibor prior to the Holocaust. After the war, though, Tibor says, Martin really came through for him and was a tremendous help. By the time Martin was able to write back to Lillian Robbins and Tibor, Tibor had already gone to England with a group of boys from Kloster Indersdorf.

While Tibor was in England, Martin worked diligently to bring him to the United States. He even went to visit Tibor in England in 1947. Tibor worked as an apprentice photographer in England and went to photo school five days a week. In 1949, Tibor married a Hungarian woman who was working in England as an au pair. Tibor’s immigration visa finally came through, and he and his wife arrived in the States in June 1950. When he became a U.S citizen, he changed his surname from Munkácsi to Sands. Sands was the first name his finger landed on when he opened the phone book to choose a new name.

When they arrived in the States, Tibor had a difficult time finding a job. His brother Martin was now in bad shape financially, and Tibor worked for a while as a tailor in a sweatshop in New York. In 1951, he landed a job with a fashion photographer. For the next eight years, he worked with him as a studio manager and assistant.

Tibor’s brother Muki was also a photographer. He worked in the film industry and helped Tibor to make professional contacts. Tibor became a still photographer in the motion picture industry. He could not get membership in the union and could only work when union members were not available. He took the pre-production still photos for the film West Side Story. One day, someone suggested he become an assistant cameraman. “Without bragging,” Tibor says, “I became one of the most well-known, popular cameramen in the industry.” Tibor was an assistant cameraman on around 20 films, including The Godfather. He was well-liked and quite popular. He retired in 1991 and stayed retired for two years until ARRI CSC, a German camera company, offered him a job. He worked as a rental manager and then a consumer relations person. Tibor says his colleagues were all wonderful to him and laid to rest any reservations he may have had about working for a German company. He still remains friendly with many of his former colleagues.

Tibor travelled extensively throughout his career and has been to every continent except Australia. He was married to his first wife for 14 years, and they had two children: Kim, a teacher of English as a second language, and Robert, a camera operator. Tibor is now married to Sara, a computer programmer and “the most wonderful woman in the world.” He thinks that Remember Me? is “a very valuable project.”